The Quadrants of Dog Training are Nonsense

I’ve wanted to tackle the famous quadrants of dog training for a while. So here goes. I can’t avoid getting a bit technical in places, but I’ll minimise it as much as possible so I don't get bogged down.

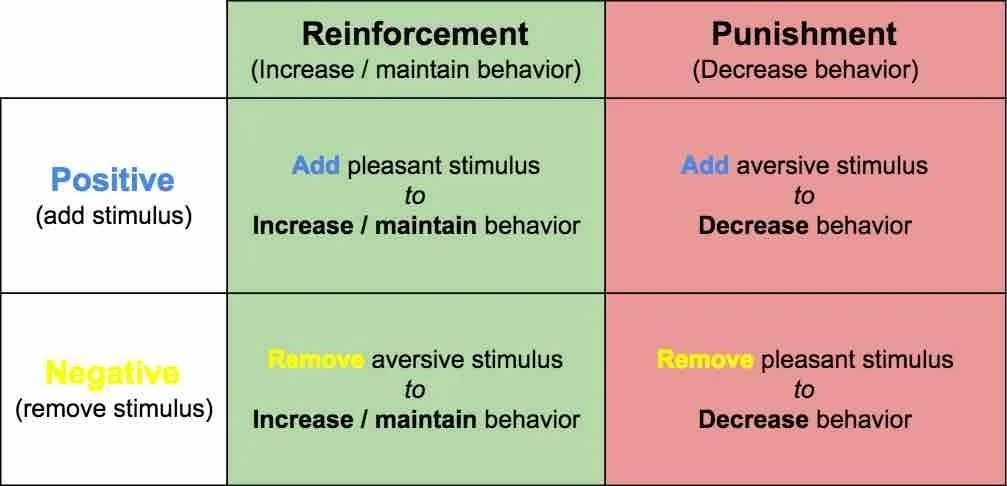

I’m sure you’ve all seen the operant conditioning 2×2 matrix known as the quadrants of dog training. I’ve included an image below for reference. In this blog I shall address why I consider the quadrants to be nonsense, in terms of dog training, and I’ll use references to scientific literature and real world examples to do so.

The Quadrants of Dog Training

First some background on the quadrants. They originated as an interpretation of Operant Conditioning as discovered by B.F. Skinner. They are often used by dog trainers almost interchangeably with the term Operant Conditioning. That is an error, though they use terminology which is directly part of the Operant Conditioning verbiage.

Operant Conditioning has a very specific definition as published by B.F. Skinner in a few of his books, the most well known book being About Behaviourism. Unfortunately there is a second definition which bears little resemblance to B.F. Skinner's and for which I have been completely unable to locate the source of in any published literature, but the erroneous version has become the default and is used in popular culture and is therefore used by dog trainers among others, perhaps because it is the one that comes up top in internet searches, I don't know, but it is a problem.

Sadly this erroneous version of the definition of Operant Conditioning is where a lot of the problems with dog training have come from. In the interests of brevity I am not going to go any further into this today, Operant Conditioning is a big blog topic of its own. This blog is specifically about the quadrants.

I do find it curious that in About Behaviourism, Skinner's paragraphs describing Operant Conditioning end by describing how punishment can temporarily stop behaviour but does not stop the intent of behaviour, so in the future the punished behaviour will return unless the punishment is presented or the threat of it is present permanently.

What does that mean exactly? Put another way, it means punishment doesn't work to change behaviour, just temporarily suppress it - this was proven scientifically. Exactly how the person(s) who came up with the quadrants didn’t pick up on Skinner’s refutation of the very concept of punishment being effective in changing behaviour is beyond me. We shall dig into this in more depth in a bit.

First we need to establish definitions for terms:

Reinforcement:

Positive reinforcement: When a type of behaviour has a consequence called reinforcing, it is more likely to happen again. A positive reinforcer strengthens any behaviour that produces it. Example: A glass of water when you are thirsty is positively reinforcing, if you do something that gets you a drink of water when you are thirsty, you are more likely to do so again on similar occasions.

Negative reinforcement: A negative reinforcer strengthens any behaviour that reduces or terminates it. If your shoe is hurting your foot, the relief from pain in taking off the shoe is negatively reinforcing, so you are more likely to take off the shoe next time it hurts your foot.

Hopefully that’s so far so good. You should be able to correlate those two types of reinforcement with the left hand column of the matrix, in the green boxes.

The ultimate state of positive reinforcement is when all your needs are met; food, water, shelter, a mate, no stress in your life, you’re achieving everything you want, everything is calm and easy. You are relaxed, satiated and happy. This is what we are all striving towards. There is a deeper step into positive reinforcement, with a serious dark side, but that’s a topic for a different day, this definition will do for now.

Let’s now tackle why things are reinforcing. A common misconception exists, and in fact I’ve used that exact misconception above in the negative reinforcement definition, in why things are reinforcing. The misconception is that reinforcement exists because it feels / tastes / smells good. That is actually secondary. The reason reinforcement exists, and where it comes from is deeper. Mammalian behavioural reinforcement has developed and exists as the underpinning survival mechanism for both the individual and the species. Everything that we find reinforcing can in some way be traced back to a related survival and / or mating mechanism. Avoiding pain prevents injury, in turn allowing survival, mate finding and reproduction. Being able to source food and water on demand provides the best opportunity for both survival of the individual, their mate(s) and offspring, thus the species. It therefore follows that being successful at these activities is reinforcing as everyone wants to survive, and most want to reproduce.

Historically with survival of the fittest, only those at the top of the survival, resource gathering and protecting games could mate. You can take this to the Nth degree; the foods that make our mouths water are those that evolutionarily are the most important and difficult to obtain, again, its survival related, and all lead toward the ultimate state of reinforcement.

Let’s now turn to punishment. I’ll have to get a bit technical here, paraphrase some Skinner and the quadrants of dog training;

The stimuli that function as reinforcers when they are reduced or removed, can be thought of as aversive stimuli, or punishing stimuli. The punishing stimuli, in terms of the quadrants can be thought of as the opposite of reinforcement, they are designed to reduce or remove behaviour, not increase it.

The problem is that when that theory was tested, it didn’t hold true as I’ll demonstrate below.

Positive Punishment: Smacking a child to stop them from doing something again.

Negative Punishment: Putting an offender in prison (for smacking a child???) is a negative punishment – you could think of this as taking away freedom.

In the positive punishment example above, B.F. Skinner ended up determining that it could not be technically distinguished from presenting a negative reinforcer, despite saying that punishment is easily confused with, but different to negative reinforcement. Bit strange, no?

In the negative punishment example, B.F. Skinner could not technically distinguish it from removing a positive reinforcement. Very odd indeed. What does that mean then?

It means that by design and definition, punishment is not reinforcement, but, in a technical sense, in terms of analysing behaviour in experiments, the very person who coined the terms, along with Operant Conditioning, could not technically distinguish between the boxes of the quadrants (which didn't exist when Skinner was working) positive punishment and negative reinforcement, nor could he distinguish between negative punishment and removal of positive reinforcement. The reason for this I’ll get into below, but for now, the lesson to take away is that removal of your positive reinforcement – is punishment - BUT - because the removal of positive reinforcement is actually a negative reinforcement per Skinner in Behaviour of Organisms, it drives you to do behaviours (negative reinforcement increases behaviour, remember) that will return you to positive reinforcement, be that via fighting the punishment, seeking a work around, or stubbornly doing nothing until a suitable opportunity to avoid the punishment and do the behaviour presents itself.

So, anything that takes you away from, or prevents you getting to your goal of the ultimate positive reinforcement, or any positive reinforcement, is punishment, but that punishment will never stop you from taking steps to achieve your ultimate state of reinforcement. That’s a lot to take in, I know.

Example: If your positive reinforcement is to meet that dog over there to determine if they are friend or foe (survival and / or mating based reinforcement), and your handler stops you and shoves a treat in your face as an alternative reinforcement, they are by definition punishing you by removing your ability to achieve your positive reinforcement. Worse, it can be viewed as rewarding punishment when the treat is considered in the equation. There’s some good words for when we “pay” someone to do something for us that they don’t really want to……. Bribery / manipulation spring to mind. Not things that form the foundation of great relationships are they.

Let me pose this question; How can the quadrants make any sense, when behaviourists can’t design any experiments that can tell when you aren’t in the left hand column of reinforcement when testing and analysing behaviour? Bit of an issue when determining what works and what doesn’t.

Here is the crux of the problem:

According to B.F. Skinner in About Behaviourism: [I’m paraphrasing] If the effect of punishment were simply the reverse of reinforcement, a great deal of behaviour could be easily explained. Unfortunately, this is not the case, when punishment is administered, the punished person (or dog, or any mammal) remains inclined to behave in a punishable way, but punishment is avoided by doing something else instead, often nothing more than stubbornly doing nothing.

Let me put that into a real world example for you. I used to use a slip leash on my dog, Rollo. Just in case you don't know, a slip leash works by strangulation, when the dog pulls on the leash, it tightens around the neck, choking the dog. This, in the quadrants makes it a positive punishment (or presenting a negative reinforcement if you prefer to stay away from the quadrants). Why did I use this tool? Because he did things like lunge at dogs he wanted to meet, ignoring my commands to leave it. Meeting other dogs was (and still is) Rollo’s positive reinforcement, he loves it. Having Rollo wear a slip leash I managed to get Rollo to be able to walk directly by other dogs on the street and not do anything except keep walking. I didn’t know this at the time, but Rollo was stubbornly doing nothing every time he walked past another dog and ignored it. I had Rollo in this tool for two years. I met Robert Hynes somewhere around this point, and Robert told me punishment doesn’t work, citing the Skinner text I’ve paraphrased above. So I took Robert’s challenge and took the slip leash off Rollo, swapped it for a flat collar and went to town. What did Rollo do to the first dog we came across on that walk after 2 years in a slip leash? He lunged at it with full power against my holding the leash in a desperate attempt to meet the dog. Rollo repeated this with the very next dog, which was humiliating when the other owner asked me if Rollo was my new rescue dog.

What’s my point? Rollo’s behaviour followed exactly as B.F. Skinner stated it would in About Behaviourism. The punishment Rollo was subjected to for two whole years did not change Rollo’s desire to do the behaviour of meeting other dogs one iota. Not in two years of being strangled every time he acted on his desire did it change. The very moment the "positive punishment" (or negative reinforcement in actuality) was removed, the original behaviour returned, and with some serious force. Rollo was meeting that dog and there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it. Rollo knew this too. He knew I couldn’t stop him getting his positive reinforcement so it came out in the full explosive display of a Tibetan Mastiff.

If we stick to the quadrants a moment, think on this; if your dog is doing behaviours that you don’t like, if you try and extinguish those behaviours via punishment, you will have some success at stopping them, BUT, you will have to employ that punishment for the rest of the dog’s life because you cannot and will not change the desire of the dog to do that behaviour by punishing it. It is scientifically impossible. As soon as the punishing control mechanism you have used is either taken away or not present in the environment, the original behaviour will return, and likely stronger than before. That is a fail in changing behaviour.

So what is the point of the punishment side of the quadrants above if they don’t work to actually change behaviour, and even worse, they don’t technically exist according to the Professor who discovered Operant Conditioning? Well, if you note the language of trainers and people who use the quadrants, they use the words “modify behaviour” instead, which is a trick. Yes behaviour can be modified, but it cannot be permanently changed by punishment – ergo the punishment side of the quadrants only make sense if you intend to control the dog’s unwanted behaviours in every situation that they might occur, for life. That distils down to control, always and everywhere, for life. Can you see the appeal of an e-collar now - punishment and behaviour suppression on demand.

The two punishment parts of the quadrants are therefore about control, and only control. There is no room for anything else, otherwise the behaviour returns, as I've demonstrated. This is why people using punishment need treats, slip leashes, prong collars, e-collars, etc for life. The threat of punishment must be ever present for it to work.

If you want to permanently change your dog’s behaviour, the two punishment quadrants have to be shunned, they cannot exist for you. The only way to change behaviour permanently is to change the emotional feeling that is causing the behaviour (I’ve written a blog on that exact topic, handily for you…….) to a positive reinforcement that causes them to do something else instead.

Only your dog can change their emotional feeling and therefore behaviour, via operant conditioning, which as I’ve mentioned, under B.F. Skinner has a very different look and definition to the one that spawned those damn quadrants, which I can't find the source of, and which don’t technically exist in changing a behavioural repertoire.

The reality of the quadrants is that by applying the terms contained within them to your dog, all of those terms fit very neatly into manipulating, with varying degrees of physical force and / or mental coercion, the dog to do something. That's not a healthy foundation for a relationship with man's best friend. That’s a tangent for another blog (is that 3 new blogs I’ve talked myself into in this one?), but have we really got to a stage where we are told by professionals that we have to manipulate our dogs to do things for us that they’ve done for tens of thousands of years without said manipulation?

The answer is no, we don’t need to do that, we do however, need to understand that punishment doesn’t have any permanent effect on behaviour, is technically / scientifically indistinguishable from the removal of positive reinforcement, and that only your dog can decide what is positive reinforcement and what is negative reinforcement and therefore punishing, in each situation, you cannot do that on your dog’s behalf, thus, I conclude, the quadrants of dog training are nonsense and should be discarded as the junk interpretation of science that I've demonstrated they are.